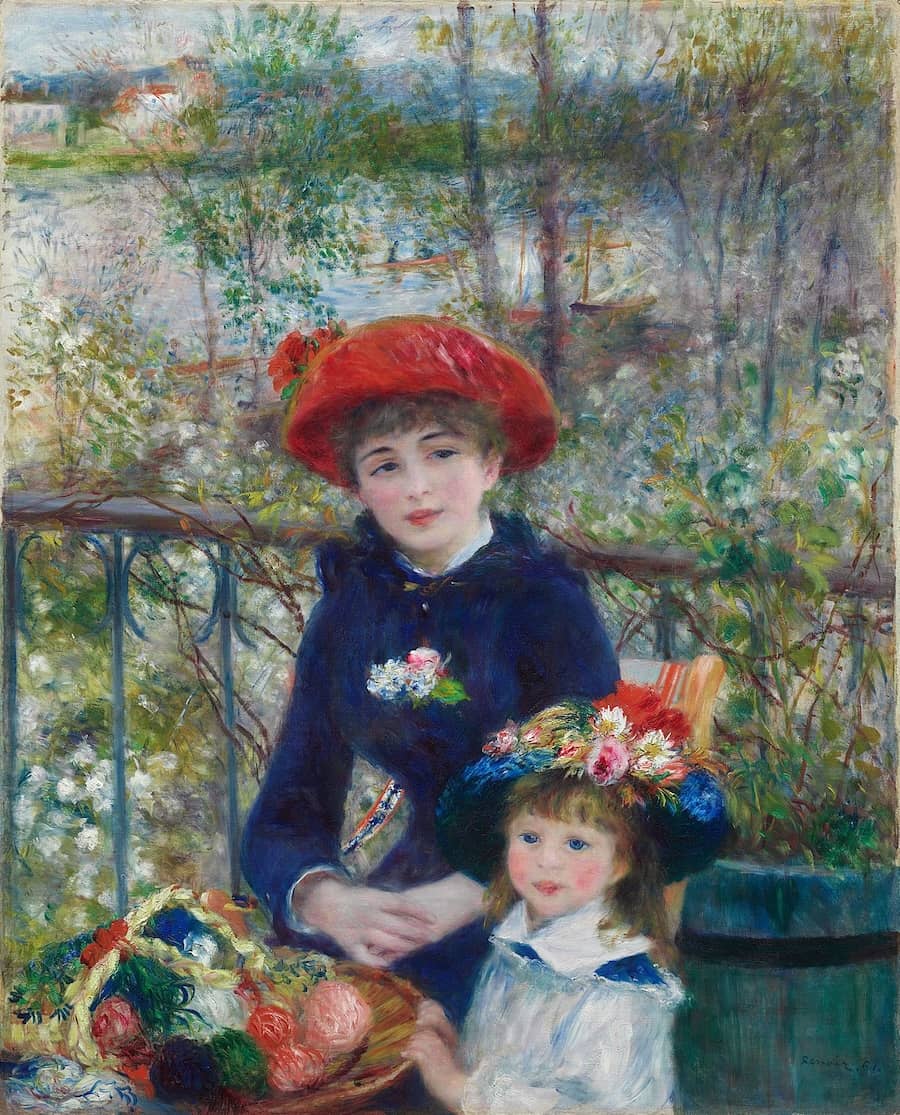

Two Sisters - by Pierre-Auguste Renoir

In the most Literal sense this composition derives from the traditional devices that often served as a point of departure for Renoir's basic arrangements. The young woman and child and the sewing basket form a pyramid in the time-honored usage of generations of earlier paihters. Also traditional is the balustrade, which sets off the figures from the background and lends a degree of architectural firmness to the otherwise complex irregularities of form. It was Renoir's gift, however, to be able to sustain his originality despite his respect for the accepted usage. That balance between tradition and invention is here masterfully exploited.

The figures seem immediate, caught in a particular moment. Their informality is brought out not only in the pose but in the extreme forward placement of the little girl; almost as a fragment, she appears to peek over the bottom limits of the frame. So too the basket of yarn and the green plant bucket to the extreme left. All seem crowded - almost prodigally - into an overflowing foreground. The terrace rail, set at a glancing angle, similarly disclaims the curse of dry geometry. Though it marks off a private corner in the shady park along the Seine, its thin and penetrable forms also provide a transition to the open tapestry of landscape behind the pert young woman and the winsome child. Trailiag vines interlace with the rail and its slender metal supports, while at the right, the balustrade and potted plant become as one. In another order of relationship, the trunks of the trees in the middle ground echo with varying precision more regular man-made shapes. In ways like these, we can observe how the artist retained a sense of disarming simplicity in his canvas despite the complexity of his forms and color. The artist said:

I arrange my subject as I want it, then I go ahead and paint it like a child. I want a red to be sonorous, to sound like a bell; if it doesn't turn out that way, I put in more reds or other colors till I get it. I am no cleverer than that."

The notion of arrangement is apparent; so too the deep trust in the worth of the thing observed. What is missing from this or any other "explanation" is the intuition that directs the selection and emphasis. Nowhere else has the painter found a red more "sonorous." But is it the red of the hats and yarn that is the directing force, or is it the opalescent tints of the flesh or the gleaming white of the girl's dress as it is contrasted with the deep blues of the other dress, or the filmy greens of the trees that stand open to the sky? No, it is not any one of these but all in their harmonious ensemble that have been the artist's tools in accomplishing his final aim: to conjure a blossoming glade, where a small girl and her friend are discovered quite by chance in a moment of quiet contentment.