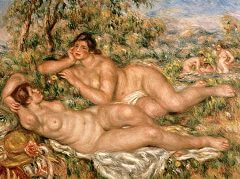

Three Bathers - by Pierre-Auguste Renoir

In Three Bathers Renoir seems almost to pay a gracious compliment to the great decorators of the French eigh-teenth century, whom he continued to admire throughout his life. He made no secret of his affection for the lyric softness of Watteau or the adroit playfulness of Boucher. But this gesture (if such it may be called] is the more appealing for its independence, for Renoir's appreciation was too profound to allow him to fall into empty eclecticism. Though his terms were very different from Cezanne's, Renoir's goal in this respect at least resembled that of the Master of Aix: to bring tradition up to date; to relive it within the immediate demands of his own creative personality.

Although the subject appeared frequently in Renoir's oeuvre, this particular version of the bathers theme is one of his happiest achievements. Its gay spirit is infectious. Its limpid color harmonies and surging movement seem bafflingly effortless. Taken literally, however, the subject matter is trivial enough: a nude girl at the center of the composition teases one of her companions by holding out what appears to be a small crab. The second girl recoils defensively, while the others - a seated nude to the left foreground and two wading women in the middle distance-turn to watch the play. Fortunately this narrative incident was Renoir's starting point and not his end, so that what for a lesser artist would have remained a banal anecdote became instead an intoxicating vision of robust forms enveloped by a pearly morning light. It is almost as though a stage scrim has been dropped between the spectator and the performers, to enlarge and abstract the whole scene by the suppression of irrelevant detail.

Yet there is no lack of richness in the development of the forms, as with a caressing stroke of the brush the artist loads his paint onto his canvas. Nor is he unaware of subtle color differences as he adds a note of sharp red in a drape or counters the cobalts of the sea and sky with the blue-greens of the robe caught between the two cavorting figures. He differentiates the complexions of his three major figures to make each more individual than she may at first seem. And the colors of their glowing bodies are transposed into the landscape, where added notes of green suffice to convert them into a new context without loss of a sense of underlying affinity. Thus, with cajoling craft the painter disciplines his subject, training its rhythms and coaxing its colors into obedience. With patient yet hidden care he works out an exciting visual balance that lends breadth and vitality to a sense of carefree, simple abandon.